African history through the eyes of a child

How Ekiuwa Aire and ‘The 1619 Project’ educate all from childhood to adulthood

Three years. That’s how long it took me to read the New York Times “1619 Project.” It’s not that I wouldn’t find it interesting; I genuinely thought I was going to know most of the information inside of it. When you’re reading Alex Haley’s “Roots” and “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” by the time you hit sixth grade — and going on field trips to see the latter movie in theaters — a student like me becomes fairly confident that she knows a healthy amount of information about African-American history.

An annual promo for NYT crossed my desk. I signed up for it. And curiosity made me scroll around to look for something new in the report that has had anti-Critical Race Theory activists falling all over each other to get this research project to disappear. A smile lit across my face when I got to Mary Elliott and Jazmine Hughes’ article on “the history you didn’t learn in school.” In the middle of the page was a hand-colored lithograph of Queen Njinga. She is a woman I got to know quite well, courtesy of a book editing project with the author of “Queen Njinga”: Ekiuwa Aire.

Recommended Read: “Black book characters make black kids like me want to read more ~ Why Young, Black & Lit is onto something with its literature nonprofits”

After I finished reading every word of “The 1619 Project,” I kept coming back to this image of Queen Njinga and thought of a comment from an ex-boyfriend: “You love to point out how your elementary school taught black history,” he said to me. “But public schools act like black people’s history started with slavery. Like kings and queens and everyday people didn’t exist before then.”

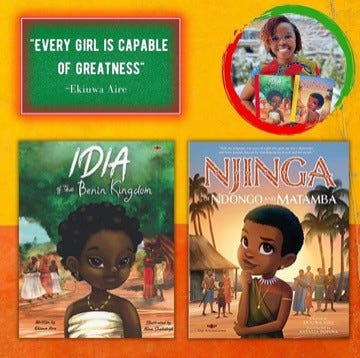

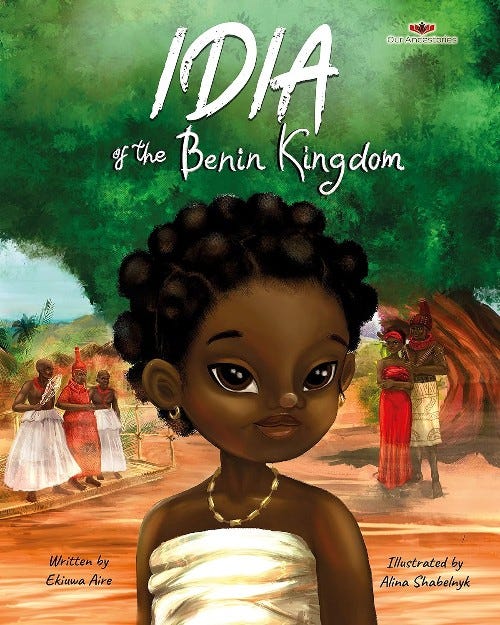

Ooof! He wasn’t wrong. But it wasn’t until I was hired to edit her two picture books — “Idia of the Benin Kingdom” and “Njinga of Ndongo and Matamba” — and a 40-week workbook that I really took his comments seriously. While I could easily talk about African-American history, I struggled to tell you five fun facts about anything pre-slavery until I met her. This leads me to my one-on-one interview with the author. We discuss her books, her international background, the myth about Africans battling with African-Americans, and Critical Race Theory. Enjoy!

ADVERTISEMENT ~ Amazon

As an Amazon affiliate, I earn a percentage from purchases with my referral links. I know some consumers are choosing to boycott Amazon for its DEI removal. However, after thinking about this thoroughly, I choose to continue promoting intriguing products from small businesses, women-owned businesses and (specifically) Black-owned businesses who still feature their items on Amazon. All five of my Substack publications now include a MINIMUM of one product sold by a Black-owned business. (I have visited the seller’s official site, not just the Amazon Black-owned logo, to verify this.) If you still choose to boycott, I 100% respect that decision.

The books: Queen Njinga, Idia and beyond

Shamontiel L. Vaughn: I was so excited when I read one of the chapters in the 1619 project, and Queen Njinga came up. I remembered the conflict with her brother and her having to flee away from the Portuguese, then ending up being the ruler of Matamba. I was so happy that when I saw her picture, I said, “ I know this story already.” And interestingly, I would have not known her story without reading one of your books.

Ekiuwa Aire: Isn’t that fascinating? That’s great!

SLV: The way you wrote the story was from a perspective that was more digestible for children to understand. What made you decide to write this story for children?

EA: I don’t think it’s rocket science. We, as black people, all over the world should understand the greatness that runs in our blood. Understand that a lot of the narrative about us is about what we achieved in the past. I think it’s deliberate to limit us regarding what we can achieve in the future. For all black people everywhere, just knowing you come from greatness — not the anecdotal stuff like telling black girls that they’re “magical” — I wanted to make it concrete. I don’t want to tell you fairy tales. That was why I wrote these books. I wanted to have it ingrained in our minds. It doesn’t have to be a mantra or mindfulness. It’s not make-believe.

Recommended Read: “Life before slavery: African history gets the silent treatment in U.S. schools ~ Teaching U.S.’s mistreatment of Africans is important, but what about pre-slavery?”

SLV: One of the hot topics these days is Critical Race Theory. It’s supposed to be for grad schools, but certain states want to ban any kind of history that isn’t fairy tales and pom-poms and great and wonderful. When I was a kid, I learned so much history that was hard on the ears and the eyes. I feel like by me learning the uglier side, it toughened me up mentally and made me be prepared through the years.

EA: Where did you learn history?

SLV: My elementary school and high school were all about like African-American History and African-American Literature. It wasn’t buried the way it is in some schools. I was talking about Jim Crow. I was talking about slavery. We watched the entire “Roots” series and read the Alex Haley books. And that was before I graduated from eighth grade.

I don’t understand the criticism with Critical Race Theory, even for children. I felt like if I could handle it when I was in elementary school, other kids that are my age then should be able to handle it to too. To put it bluntly, I feel like your kind of book will be banned. It tells the truth. And it talks about some controversy. Do you think kids should read these kinds of books anyway?

Recommended Read: “Condoleezza Rice is getting my tuition funds back ~ Critical Race Theory and her anti-‘feel-bad’ stance for white kids”

EA: I’ve heard that! Interestingly, I have been very fortunate. When I said I was gonna write my first book years ago, I got feedback from well-meaning people. “Oh, that’s awesome. Oh, that’s a great idea to write these books!” “I can see you in schools and everything.” Just being the logical person that I am, I thought, “Why would I, in my adulthood, decide to write a book and my book end up in schools?” I didn’t see that happening.

SLV: You did not see it happening?

EA: I didn’t see it happening. I’d never done this before. I have a full-time job that’s not writing books. But I did put my all into my books. Both of these books have been welcomed in schools — to thousands of kids, mostly non-African or of African descent. Those are the schools that have the funding to pay for author visits.

Recommended Read: “Social media: The pen pals we’re using wrong ~ An argument for why teachers should let students use their smartphones more — and wiser”

EA (cont.): It hasn’t felt uncomfortable reading my books. What I have noticed and what I have experienced are teachers, mostly, and kids who are welcoming this information that they’ve never heard of before. They are glad that somebody is finally breaking it down to a level that they can understand.

ADVERTISEMENT ~ Amazon

As an Amazon affiliate, I earn a percentage from purchases with my referral links.

I know that the Njinga book does call out the Portuguese. At the time, they were colonizing Angola. At one of my author visits, a young girl asked me a question. She said, “My parents are Portuguese. I don’t understand why we were so bad.” I said, “This is something that happened a while back. It’s not just the Portuguese that did it. Even Canada experienced British colonization. It’s something that countries shouldn’t do, but it’s something that countries have done.” Presenting it that way is just sharing facts, and you’re expanding their minds.”

The education: Finding African- and African-American history

SLV: That’s another reason I don’t understand the hesitation with Critical Race Theory. First of all, it’s meant for grad school. So let’s get that out the way. But I was able to retain all of that information, hear it and learn from it at such a young age. I start to wonder are maybe the adults more sensitive than the children learning the information.

EA: I also get that too! With the “Idia” book, the feedback that I got was that there was “quite a bit of information and you introduced tribal marks. I don’t know if kids are able to digest this information.” My feedback to that was, “Just because something is different doesn’t mean that it is too big for a child to handle.” I always go back, interestingly, to the Bible, and my kids learning about what happened with the Israelites and Jesus Christ. You celebrate Easter. You celebrate someone being killed in the most awful way. But we cannot teach kids about tribal marks in Africa? The double standard is quite obvious there.

SLV: It’s fascinating to me that you never intended for your books to be in schools.

EA: The logical person in me wasn’t sure if anyone would even like them. I just said, “There are no books out there [like this]. I would love for them to be in schools.” But I just didn’t think that I’d be fortunate enough to have my books picked up by schools.

SLV: We would have these library book sales, and I 100% know that the elementary school that I went to would have gotten your books buy the bulk. But that has more to do with the culture of my elementary school as opposed to speaking for the Board of Education in the United States. I spent an exorbitant amount of time in libraries, trying to earn bookmarks and get books all over the place. But the books I was gunning for — none of them looked like your books. I know that’s gotten better now. But what kind of books were you reading as a youth? What made you think that kids today would want to read something different?

EA: I read a lot of Nancy Drew, Sweet Valley High. Those were the books I read as a kid, nothing fact-based. Nothing about me and my culture. I was a minority at the time reading about blonde hair and blue-eyed girls. I’m lucky that I’m still very comfortable. I’m very proud of who I am and exactly what I stand for. There was nothing in literature that made that resonate, who I was, as an African, specifically. Because you leave where you come from, and you go across the world, which is what a lot of Africans do.

Recommended Read: “That ‘scientific study’ that makes you hate your race ~ Brown-skinned girls, look past racism to own your beauty”

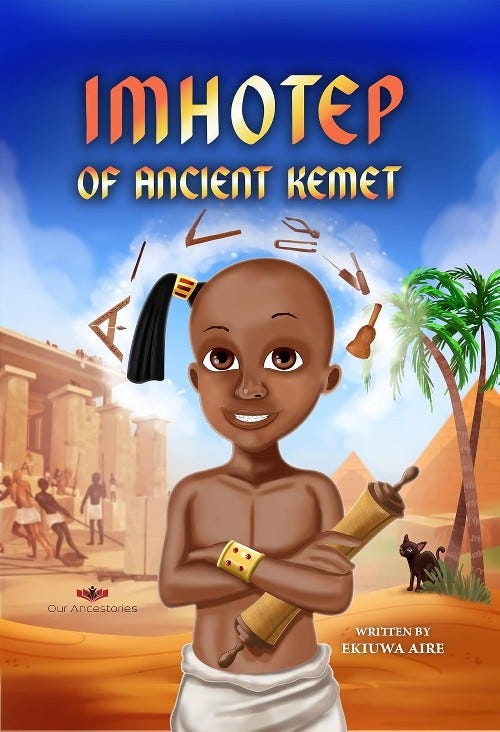

EA (cont.): I was teaching my kids about Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks, and that whole movement. While that whole [Civil Rights] movement is very important and every kid should know about it too, before then, Black people were still great and doing things on the continent. And I think it’s important that kids have a full [scope] of what happened just so it’s in their consciousness.

ADVERTISEMENT ~ Amazon

As an Amazon affiliate, I earn a percentage from purchases with my referral links.

I’m trying to create super simple books that still give you the information that you need, as with the workbook that you helped me work on. If you can just learn one lesson a day, kids will have some sort of a baseline on what Africa was really like — without some of the negativity you see in YouTube videos.

Recommended Read: “From PWI to HBCU: Why I fled ~ College, and threat of expulsion, made my naivete about racism disappear”

SLV: I learned more from editing your workbooks in the past year [about Africa] than I did throughout all of elementary school, high school, undergrad, grad school. It’s kind of sad. I appreciate the education I got. It’s paid my mortgage. But there’s a part of me that really appreciates that you even reached out. I don’t remember whether I applied or was I invited. I’ve gotten so much richer information that I just wasn’t getting before and didn’t even know to look for it. I can’t say enough about your books. They’re beautifully written. The illustrations are great.

The background: Nigeria to U.K. to Canada

SLV: Did you spend your youth in Nigeria or Canada?

EA: I spent most of my youth in Nigeria, from zero to nine. Then I spent four years in the United Kingdom. I went back to Nigeria at 13. And I came to Canada in my early 20s. I’ve been in Canada since.

Recommended Read: “For the culture: How travel can be the best history lesson ~ Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Native American history, other lessons learned in Canada”

SLV: I’ve been to Canada a couple times. I’ve been to Toronto. I’ve been Ontario. The United States is branded like this melting pot, where we have some of everybody. I’ve lived in Chicago, born and raised here, although I’ve lived in two other states for college. Chicago is very multicultural but segregated. Black people are on the South Side. White people on the North Side and suburbs. You have a segment of black people in the West Side, largely a different economical group. And the East Side is basically the lake.

There are very select pockets where people live. It wasn’t until I moved to the North Side before I started seeing a little bit of everybody. I have a neighbor right now who is from Ethiopia. A couple of blocks away, there are two or three whole blocks with Mexican-owned businesses. Other neighbors are from Bolivia in South America. My own condo association is like looking at a map.

Recommended Read: “Handling the language barrier between residents ~ Why I won’t stop sending emails in English, Spanish and Amharic”

SLV (cont.): I bring that up because when I went to Canada — Toronto and Ontario — for a Black History trip with the Girl Scouts, I saw a little bit of everybody hanging out. I very seldom saw one group only with its own group. Was it culture shock for you coming from Nigeria to Canada? How did you feel about coming there?

EA: I spent about four years in the United Kingdom before I came back to Nigeria. I had experienced living as a minority, or living in the western part of the world, in the U.K. Primary school and secondary school was tough for me at that time because all the groups hung out together. There weren’t a lot of Africans, and the black [Americans] didn’t quite want me to be part of that group. When I was ready to leave Nigeria again, I definitely did not want to go back to the U.K. From what I saw on the news, I didn’t want to come to the U.S. either.

Recommended Read: “If you’re not a minority, why are you so sure of your anti-racism tourism? ~ White people, please stop telling me to leave America to escape racism”

EA (cont.): Canada, so far, has not had this glaring division. People are more welcoming. You can all just blend in — the way Egypt was before. Nobody saw race; it was just a bunch of different people. I’m not saying that nobody sees race in Canada. It’s not as glaring as it is in the States. Everybody just hangs out.

SLV: Have you been to the United States at all?

EA: I have. I felt the race issue when I was there. I was in Baltimore.

SV: I don’t know enough about Baltimore to speak on it. All I know is “The Wire,” which is not the greatest example.

EA: What I remember was going to the park, and there were a few other moms there. I was trying to be friendly. I got the feeling they viewed me as bourgeoisie because of the way that I speak, but I can’t help that.

SLV: Were they black?

EA: Yes, they were black.

ADVERTISEMENT ~ Amazon

As an Amazon affiliate, I earn a percentage from purchases with my referral links.

SLV: Interesting. You said something earlier about the divide in the U.K. I’ve had this discussion before about African-Americans and Africans. I don’t know who started this rumor, but they’re keeping it going: That African people and African-American people don’t get along, and African people don’t want anything to do with us. And that is so bizarre to me because I’ve had friends through the years who were African. I’ve had pen pals who were mainly Ghanaian and Nigerian. My lawyer is West African, from Liberia. If Africans are supposed to act like they hate us, they’re doing a terrible job of hating me.

Recommended Read: “Black girls and Girl Scouts: It’s more than selling cookies ~ From girl’s guy to Girl Scout”

EA: Thank you! My sister and I were talking about this. We’re looking at this Twitter feed and Clubhouse about Africans looking down on African-Americans. Where? Honestly! Take a Black American to any African country. You will be worshipped. We are the most welcoming people to our own detriment. I don’t know where this is coming from.

SLV: There was a recent conversation on Twitter Spaces. That was also something that just kept coming up — the divide between Africans and African-Americans. I went right back to the same example, people who I have worked with, befriended. All I could say is, “Either they don’t know where Chicago is or they missed the memo ’cause they don’t hate me!”

EA: We need to unite, unite, unite. I hope we don’t keep [believing this myth].

SLV: 100%. Who I do business with, who I talk to, just trying to get to know people — hence the reason I had 50 pen pals. My whole goal was to meet people who do not look like me, walk like me, talk like me, dress like me, who weren’t me. I feel like if you only talk to people who are a mirror image of you, that is all you will ever know.

Writer’s note to Black folks: This interview has been a long time coming and was a pleasure. Although the interview ended by me saying to get to know people who don’t look like a mirror image of you, when it comes to literature, entirely too many African- and African-American readers in the U.S. don’t have that historical luxury. That’s a problem. While I vehemently agree that U.S. slave history, Jim Crow and other topics in Critical Race Theory should be taught, Ekiuwa Aire’s books (and other books like it) should get their time to shine. This is when we actually do need to see more people who look like us — to get a broader sense of our history before the Middle Passage and to understand our worth.

If you’re interested in finding out more about her and her work, click here to visit her official website. Follow her on Instagram, Pinterest, Facebook and Twitter, too.

Did you enjoy this post? You’re also welcome to check out my Substack columns “Black Girl In a Doggone World,” “BlackTechLogy,” “Homegrown Tales,” “I Do See Color,” “One Black Woman’s Vote” and “Window Shopping” too. Subscribe to this newsletter for the weekly posts every Wednesday. Thanks for reading!